The freedom in constraint (and why less really can mean more)

We have recently been talking to a marketeer who works for a global food brand. Conversations in their team have increasingly turned to the topic of “thoughtful indulgence” and encouraging more measured and restrained enjoyment of those snacks and treats that healthcare professionals say we should be avoiding. It’s about “creative approaches to portion control”, the “signposting” of nutritional information and “celebrating a moment to savour” over mindless scoffing. Global corporations don’t have a habit of doing things like this without being forced to and, in this case, regulations on high fat, sugar and salt foods, designed to tackle widespread obesity, provide the catalyst.

Perhaps surprisingly, in research the idea has gone down a storm with chocoholics of all shapes and sizes. Is it possible that, deep down, we all subconsciously crave some restraint and limitation? Child psychologists tell us that kids misbehave in order to test boundaries, not because they are intrinsically feral but because they want to understand the safe and acceptable space in which to play and express themselves. Knowing the limits creates its own freedom and contentment. And as the Dalai Lama once said, “self-discipline will set you free”. There’s a brilliant paradoxical tension at work here.

So while the “super-size-me” food culture isn’t going anywhere fast and the decadent lifestyles of the uber-rich continue to fill our screens, are we, just maybe, on the verge of a slow but sure shift, at least in western developed nations, from a fascination with the idea of excess? Excess calories and excess choice mean excess waist and excess waste. And are inter-related political, social and economic forces at work here?

Many political commentators have spoken about the demise of neo-liberalism. This began in the 1980s under the political leadership of Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher in the UK and was characterised by financial deregulation and the unhindered global movement of money, labour, resources and goods. It was all about creating the perfect environment for growth and wealth creation. Critics say it led to a global financial crash, widespread financial corruption and a dramatic increase in social inequality. The “Wolf of Wall Street” was the perfect tale of unrestrained ambition, indulgence and excess. Now neo-liberalism is supposedly being overtaken by nationalism and “populism”, where politicians are replacing an obsession with global trade with a celebration of national identity and protectionist policy. It might have some darker dimensions but the tacit message is “let’s celebrate who we are, where we are and what we have”. In short, it’s saying, let’s make our world smaller.

It’s now two years since the first Covid lockdowns. The pandemic made all our worlds physically smaller, limiting our movements, our personal contact, our choices and our ability to express ourselves through the things we consume and experiences we pay for. But this restraint created a greater appreciation of family, community and shared values. Despite widespread personal tragedy, covid constraints drove creativity and analogue pleasures over digital ones – dog walking, scratch cooking, sewing, communal-box-set binging, the fancy-dress family dinner party. The suspension of international flights was a shot in the arm for domestic tourism all over the world. As our horizons were reduced, we started to cherish everything that was closer to home.

And now the post-Covid business hangover has created havoc with global supply chains, reducing availability and choice whilst increasing prices. In the UK it’s further exacerbated by post-Brexit trade “friction” across previously fluid European borders. Many European-based companies will no longer deliver to the UK. That wine we used to buy directly from a merchant in Portugal now takes 4 weeks to arrive rather than 10 days and comes with an invoice for excise duty. This kind of consumer constraint in price and choice has paid dividends for the once self-apologetic UK wine industry. The increase in at-home drinking during Covid and a renewed appreciation of all things local has resulted in phenomenal growth.

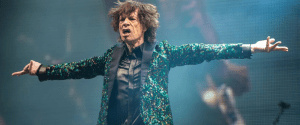

In simple terms, constraint and limitation bring focus, demand ruthlessness and perhaps counter-intuitively, free the imagination. Back in the 1960s the Rolling Stones became one of the defining bands of their generation. This was in part due to the unique stage presence of Mick Jagger. His staccato movements and strange high step dancing remains the much-imitated physical signature of the man and the band. But Jagger didn’t invent this from a blank sheet of paper. It was a direct result of the minute stages the Stones began their career performing on. Mick found that in order to dance, he had to pick his way around the speakers and equipment and captured the absurdity of this in his dancing. The beauty was born of the constraint. The rest, as they say, is history. When someone writes a song about your dancing, you’re nothing short of a legend.

That’s why, as strategists, we must give our creative cousins brilliantly tight briefs. This in turn needs the right input from our clients. As partners we need to encourage them to be equally disciplined in their thinking, their rationale and their ambitions, without letting them fall into the negative trap of focusing on what’s “realistic” instead of what’s possible.

We need to be clear which “crown jewels” need protecting, what the guardrails and “rules of the game” are and where the creative opportunity really lies. Rather than stifling creativity and beauty, a tight brief is the best thing we can do to stimulate the imagination and make creativity intentional rather than accidental.

If this struck a chord, we’d love to hear your thoughts – email newbusiness@bluemarlinbd.com